University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers are paving the way for intelligent or autonomous vehicles to communicate with the very infrastructure that lines our roadways.

The Traffic Operations and Safety (TOPS) Laboratory at UW-Madison, in partnership with the city of Madison and TAPCO, Brown Deer-based traffic safety equipment manufacturer and service provider, has created Wisconsin’s first connected corridor along Park Street in Madison.

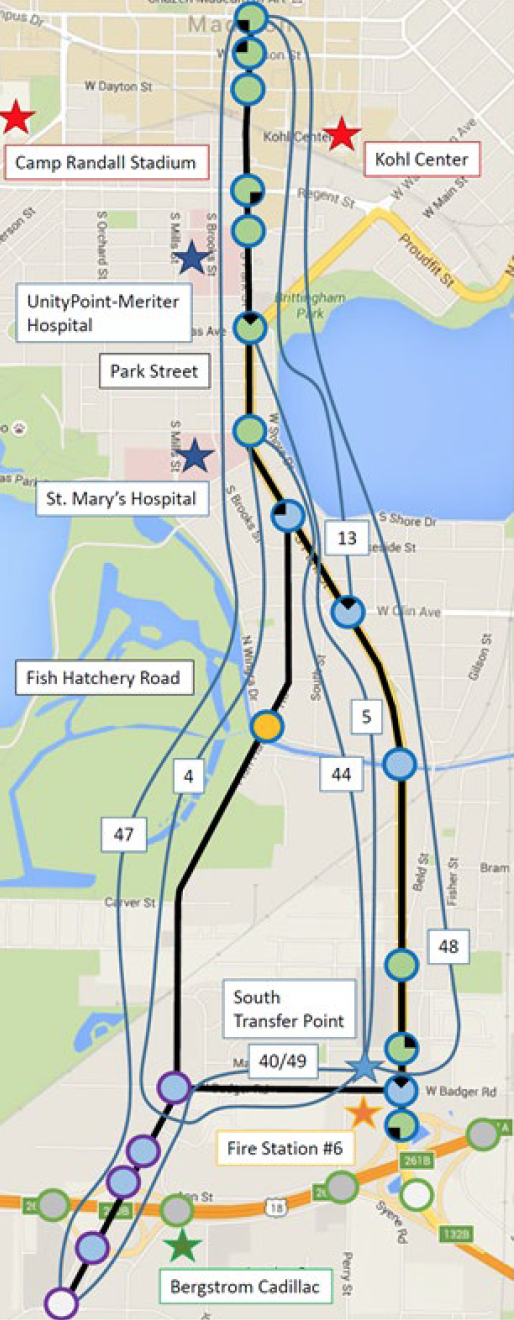

This map shows the location of connected vehicle infrastructure along Park Street in Madison. Connected infrastructure allows cars with appropriate receivers to interface with and receive information from equipment such as stop signs at intersections.

This map shows the location of connected vehicle infrastructure along Park Street in Madison. Connected infrastructure allows cars with appropriate receivers to interface with and receive information from equipment such as stop signs at intersections.

The Park Street connected corridor spans roughly four miles, from its intersection with University Avenue to its connection with the Madison Beltline (Highway 12/18). The route, which sees roughly 48,000 vehicles per day, serves as a major artery into and out of the university campus and Madison’s downtown. The project team has equipped 15 intersections along the Park Street corridor with dedicated short-range communication roadside units that form the backbone of a smart, connected corridor.

Jon Riehl, a transportation systems management and operations engineer and researcher in the TOPS Lab, says the upgrades at these intersections build on Madison’s fiber optic infrastructure and can allow the roadside units to “talk” to vehicles that have appropriate equipment as they move along the corridor. For the time being, the TOPS Lab has installed units onboard four vehicles, though Riehl says the team and city are working to expand to some of the city of Madison’s municipal vehicle fleet to collect more data.

“As the vehicles move, they transmit basic safety messages (BSMs) 10 times a second that give information about speed, location and heading,” Riehl says. “The intersection is sending back information on signal phasing and timing. So if, for example, the signal is red, it informs the vehicle of this, as well as how soon the signal will turn green. The smart signals can also send out support messages such as a map of the intersection, so an intelligent vehicle can know what lane it’s in, whether that lane is used for turning, and so on.”

The Park Street project is valuable not only as a means to collect data in a real-world connected corridor, but to provide TOPS Lab researchers opportunities to use that data to explore how to improve traffic safety and flow. Though cars capable of interfacing with connected infrastructure are uncommon now, Riehl says it will be vital to understand practical applications for the technology as connected vehicles— those that can communicate with infrastructure and other vehicles—become more broadly available. The same technology will also likely propagate into autonomous vehicles that are capable of driving themselves in some capacity, but Riehl says it will likely take much longer such vehicles to become more common.

For example, an emergency vehicle with the right onboard equipment could work with a smart corridor to more efficiently move through traffic. Riehl says such a system could adjust its signals in real time to prioritize getting first responders to their destination.

The TOPS Lab will also work on designing algorithms to make use of the data while further expanding the network. Riehl says researchers also are designing a public-facing dashboard so the public can better understand how the corridor works, and to build a data hub that allows third-party apps to interface with the system, in a way that’s similar to how apps can work with the Madison Metro bus transit network.

Connected roadside infrastructure systems also could interface with vehicles, as well as bicycles and pedestrians, to provide warnings about red lights or roadside hazards, and TOPS Lab researchers are determining the best way to convert that information into messages motorists can quickly and easily understand.

“We have a full-scale driving simulator in that we’re using for tests to see how drivers react to messages and how to best convey that information,” Riehl says. “Messages can be sent in a variety of methods, such as audible warnings, haptic feedback, or visual cues, and the timing of messages is critical. We’ll continue to work on research for those potential applications. The big question for us is this: Once we receive messages from vehicles and the infrastructure, how can we process them to best improve traffic mobility and safety?”

The Intelligent Transportation Society of Wisconsin (ITS Wisconsin), a chapter of ITS America, named the Park Street corridor project its Project of the Year for 2021. The award recognizes the outstanding research conducted along the corridor through the collaborative efforts of the TOPS Lab and its partners. The Park Street connected corridor is the largest such project in Wisconsin, in addition to being the first of its type in the state. The Wisconsin Department of Transportation is working on a similar project in Milwaukee and is working with the TOPS Lab to expand the Park Street project to the Highway 12/18 interchange.

Brian Scharles Sr., TAPCO’s director of ITS engineering and service, says the company was proud to partner with the city and UW-Madison for the Park Street project. The partnership also included working with Yunex Traffic (a Siemens company), Danlaw and Commsignia to deploy the smart infrastructure units along Park Street.

“The Park Street corridor project is exploring the possibilities of connected vehicle technology to improve roadway safety for all,” Scharles says. “The project team is gaining valuable real-world knowledge, integrating connected vehicle devices with the city’s traffic intersections and measuring the distance of wireless communication to vehicles. It’s a new frontier, and we’re working with UW-Madison to ensure Wisconsin is on the cutting edge.”