Engineers across the country are searching for ways to help communities withstand extreme weather events that are only growing stronger and more frequent as our climate changes.

Daniel Wright, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is undertaking a two-year project he hopes will strengthen the state’s infrastructure guidelines to better prepare for future extreme weather events. Wright’s work is funded through a Baldwin Wisconsin Idea Grant. Wright, a hydrologist who studies how climate change is fueling extreme weather across the United States, also co-chairs the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impact’s Infrastructure Working Group. The working group, led by Robert Montgomery, a Madison-area consulting engineering and professor of practice in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at UW-Madison, is heavily involved in the project.

Infrastructure like storm sewers, drainage systems and flood control dams are often based on their ability to withstand storms of varying intensity. These storms are measured in terms of “recurrence interval” categories, such as 10-year or 100-year storms. An “x-year” storm event refers to the probability of a certain amount of rainfall falling at a specific location during a year, and 100-year storms are more severe but less likely than 10-year ones. The amount of rainfall that defines these events varies by location—for example, a 100-year storm in Wisconsin may be wetter than one in Arizona—and data gets collected over many years and compiled to inform engineering guidelines for specific areas.

“Those statistics get used for infrastructure planning, design and regulation,” Wright says. “The issue we’re seeing is that, throughout much of the state, extreme rainstorms are happening more and more often. Because of that, the existing statistics used by the engineering community appear to be inadequate. In other words, we’re under-designing our infrastructure.”

Wright and Montgomery are working with David Lorenz from the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, as well as representatives from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, the Wisconsin chapter of the American Public Works Association, the Southwest Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, the cities of Madison and Brookfield, and a few consulting engineers.

Lorenz is an expert on climate model downscaling, which takes data from big-picture climate models and gives it the detail necessary for use at a local level. Wright says the team will use its data to predict what future needs may arise as the climate continues to change.

“That’s important because infrastructure projects have such long lifespans,” Wright says. “Typical infrastructure has a 30- to 50-year lifespan, and many will stick around for longer than originally intended.”

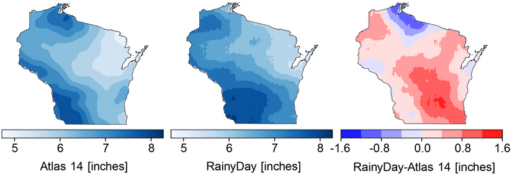

To create the updated guidelines, the team will use RainyDay, a software program Wright developed for generating extreme rainfall statistics by analyzing weather radar data. It allows for much more up-to-date statistics than federal guidelines, which Wright says were last updated about 10 years ago and, before that, hadn’t been renewed for nearly 50 years.

The goal, he says, is not only to produce updated metrics but to ensure that the work conducted at UW-Madison can be used to address the infrastructure challenges facing the state. And he says that even once the research is completed, there will be plenty of work to do to convince state leaders that stronger infrastructure is a worthwhile investment.

“It’s a challenging issue because if we produce numbers saying a 10-year storm or a 100-year storm is bigger than the federal guidelines, that means a higher cost for municipalities or other groups that have to support this infrastructure,” he says. “From the science side, this is something we can do. So we need to go ahead and produce these numbers that can help inform the conversation about how we move forward in practice.”