Steven Loheide is a professor of civil and environmental engineering who studies the interaction of hydrologic and ecological systems in the environment. He especially focuses on groundwater and how it might, for example, influence the distribution of vegetation or, conversely, how vegetation impacts how much precipitation replenishes groundwater.

In this interview, Loheide discusses the drought that has gripped the Midwest for much of summer 2023 and some of its contributing factors and impacts across the region. The good news is that it’s not all bad news.

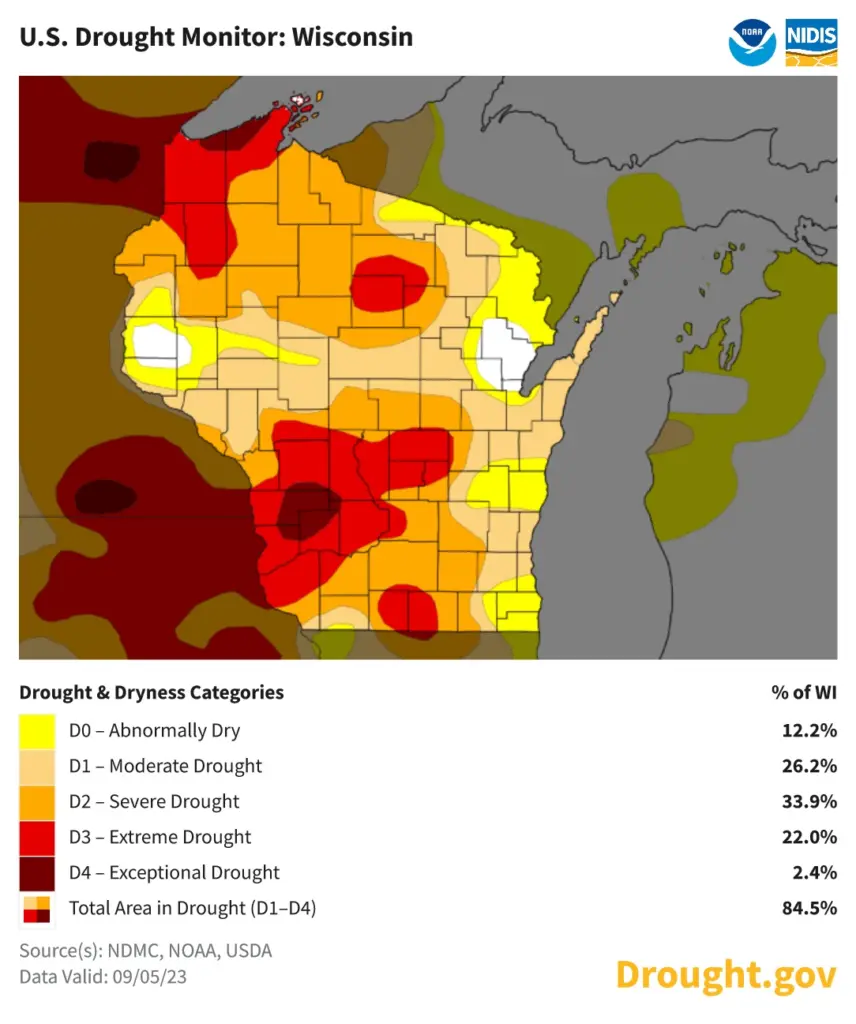

Q: It’s been an unusually dry summer. Looking at maps provided through resources like the U.S. drought monitor, we can see that this drought has impacted a big swath of the Midwest. What are some challenges we start to have with a regional drought?

A: I’d like to provide some local numbers to put some of what we’re seeing in an easier to understand context. Looking at Madison’s precipitation records, we saw 0.87 inches of rainfall in the month of May, and we normally see 4.1. In June, we saw 1.1 inches, and we normally see 5.3 inches. For July, we had 6.2 inches of rain, when we normally have around 4.5 inches, so July was actually above normal. However, in July we had two big storms that both had over an inch and a half of precipitation. In August, we had 2.4 inches of rain, compared to our average of 4.1 inches.

So there was pretty big rainfall on a couple of days in July, which is not the pattern of rainfall that we’d like to see. Getting more water with fewer, larger and more extreme events is a trend we’ve started to see in recent decades in Wisconsin.

The other really critical part of this is how it relates to the growing season. Here in Wisconsin, our rainy season corresponds with our summer months, but that’s also when plants need more water. Those two factors being synchronized is perfect for natural vegetation and for our agricultural communities. That’s what makes this drought we started experiencing in May and June potentially really hard for crops and our agricultural industry.

2012 and 1988 were the two big droughts that I’ve experienced in this region. Both of those had pretty bad consequences in terms of crop yields. We don’t know what the rest of this season holds, but the rains that we got in July have helped to make a dent and get some of those crops through. If we hadn’t gotten those, we could be in really dire straits.

Also, when you have a large area impacted like we do now across the upper Midwest and the Great Plains, it affects regional crop yields and regional prices. That’s important not only right now in the growing season, but going into next year as farmers need corn and soybeans for livestock. If there’s not enough locally produced feed, and you have to bring in more from other areas, if crop prices are high on top of increased transportation costs, that can lead to higher prices that ripple out and possibly become a longer-term impact—even if the drought itself might end, for example, in the fall.

Q: It has been interesting to watch the drought monitor from week to week after we have those big rains and thinking that it might really start to show some relief. But that hasn’t really been the case. Is it because it’s just that difficult to catch up once you’ve fallen behind on rainfall?

A: It can be, especially at this time of year, when the potential for evaporation and transpiration is so high. That makes it very hard to catch up when you’re running a deficit in the soil zone. Another challenge is that you can fall back into that drought condition much more quickly than you would in, say, the fall.

The really big extreme events, in terms of rainfall amount and intensities, are the ones that are more likely to cause flooding. If the precipitation rate is higher than what can infiltrate into the ground, then it becomes runoff, which can go into our streams and create flood pulses that can move downstream and cause erosion. So those big events might end up not doing a whole lot to help, compared to if we had more steady rain spread out over smaller events.

This drought map shows the areas of Wisconsin that were affected by drought, and its intensity, as of the beginning of September 2023. Almost all of Wisconsin, and broad sections of the Midwest, have been impacted by drought conditions that began in late spring and summer. Image source: National Integrated Drought Information System.

This drought map shows the areas of Wisconsin that were affected by drought, and its intensity, as of the beginning of September 2023. Almost all of Wisconsin, and broad sections of the Midwest, have been impacted by drought conditions that began in late spring and summer. Image source: National Integrated Drought Information System.

Q: Groundwater is important in Wisconsin; two-thirds of the state’s people get drinking water from underground aquifers. As this drought drags out, is there reason to be concerned about impacts on the state’s groundwater?

A: Our aquifers are big systems. That buffers them from short-term fluctuations, but extended periods of drought and high use can cause depletion of our groundwater resources.

The replenishment of groundwater is called groundwater recharge. In a typical year in Wisconsin, much of our groundwater recharge comes during the spring snowmelt, and relatively little groundwater recharge happens during the summer. Even though that’s when we get the most precipitation, that’s also when there’s the most demand from vegetation for water use. A lot of the rain we see in summer ends up being discharged back into the atmosphere as transpiration from water that’s been used by plants. So it’s really plants that are feeling the effect of the summer drought.

If we look back at the winter, January, February and March had above-average snowfall. In late March, we had a big rain-on-snow event, and then a big snowmelt after that. We ended up with a lot of groundwater recharge from that.

So, because our aquifers respond to long-term trends, even if they’re not being refilled right now, they’re not going to drain out super quickly because they got that big boost at the end of winter, right before the drought set in. However, when you have extended droughts, that can have an impact, and the longer one goes on, the more we might see reductions in our streams baseflow, which is the water that seeps from the ground into our streams and rivers even when it hasn’t rained recently.

Q: We discussed drought and its potential impact on farmers and crop growth. What are some other impacts we can see from these prolonged dry periods?

A: It impacts navigation. Last fall, for instance, the Mississippi River was quite low—low enough that there was a lot of concern about barge traffic moving along the river. And now again, as of July, we’re starting to see concern again from the Army Corps of Engineers such that they’re once again on the watch for potential navigation impacts from this drought.

Because this drought extends over a large portion of the upper Midwest, if the streams that feed into the Mississippi River have less water, there’s this cumulative effect. It adds up to something that could once again be a major national concern.

Droughts obviously can make the risks of fires worse when vegetation gets dry. If you’re looking for some small silver lining, when there’s less water, it keeps mosquito populations down.

But I don’t know if I’d say that’s worth all the other damage droughts can cause.

Top photo caption: Civil and Environmental Engineering Professor Steven Loheide studies how water moves through and interacts with the environment. Credit: Renee Meiller.