The Upper Mississippi River is an important component of the Midwest economy: Annually, more than $88 billion in goods travels up and down its waters.

Yet, the very infrastructure that makes this movement possible also contains many points of potential failure. And that’s a precarious situation for the surrounding states, which need to decide whether they can afford to maintain the waterway infrastructure or, in the event of a failure, take on additional expenses when other transportation modes must absorb displaced freight movement along the river.

At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a new report, “Modal investment comparison: The impact of upper Mississippi River lock and dam shutdowns on state highway infrastructure,” can help states evaluate the costs and benefits of river infrastructure maintenance and investment decisions.

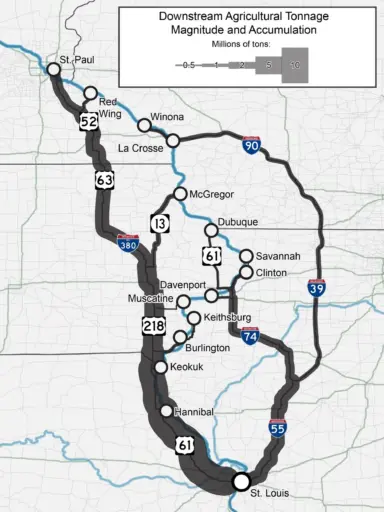

This map shows how a failure in the lock and dam system along the Upper Mississippi River would result in a cascade of accumulating truck traffic along the region’s highways. The line thickness represents the millions of tons of agricultural exports from the affected states that would be forced onto highways on their journey to domestic and international markets.

This map shows how a failure in the lock and dam system along the Upper Mississippi River would result in a cascade of accumulating truck traffic along the region’s highways. The line thickness represents the millions of tons of agricultural exports from the affected states that would be forced onto highways on their journey to domestic and international markets.

The report is the result of research conducted through the Mid-America Freight Coalition, a 10-state organization that plans, operates, preserves and improves transportation infrastructure in the Midwest. The coalition is headquartered in the National Center for Freight & Infrastructure Research & Education in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at UW-Madison. State departments of transportation are increasingly progressive in thinking about transportation infrastructure, says Ernest Perry, coalition program manager and principal investigator for the project.

“More and more they must support the whole system of transportation, including all modes, as compared to the past where they were relegated to highway management,” he says. “With this increasing scope, they are looking for ways to make the most of every transportation mode, leveraging each for the maximum benefit of their state. This means finding the data they need to make good decisions about their transportation infrastructure.”

The Upper Mississippi River is the portion of the Mississippi River between Minneapolis-St. Paul, and St. Louis. It’s an area that is navigable for freight movement on barges, which is facilitated through a series of locks. Most of this lock-and dam-infrastructure is nearly 100 years old, and maintenance of these structures is woefully behind schedule, with an estimated backlog of more than $1 billion.

The result is river infrastructure deteriorating faster than it is being replaced.

“With this system suffering from chronic underfunding, one of the biggest questions surrounding the Upper Mississippi River lock and dam system is, ‘What would the impact be if a long-term shutdown takes place?’ This report helps us broaden our understanding by quantifying the financial impact of such an occurrence to the state, trucking companies, and the environment. It also helps us target corridors that would potentially be affected if a modal shift of commodities from the waterway was necessary,” says Sam Hiscocks, freight coordinator for the Iowa Department of Transportation.

Budget constraints and maintenance backlogs also impact highways and bridges: Currently, there is an estimated $836 billion backlog in bridge and highway investment, nationally. Given the lack of investment and, in many cases, deteriorating pavement conditions, a potential shutdown of the Upper Mississippi River due to lock and dam failure would force significant river freight tonnage to be rerouted onto the highways.

Those highways would absorb significant pavement and structural damage from increased traffic of fully loaded trucks.

Coalition researchers compared the relative costs of maintaining the marine infrastructure versus the projected maintenance costs that would be incurred by the highway system in the event of failures in the lock and dam system.

Looking only at the impacts of agricultural commodities headed down the Mississippi, the researchers calculated the increased traffic to parallel highway routes that would be caused by a single lock and dam failure. With the help of maps, trends for the region emerged. The largest percent increases in highway traffic would occur in rural Minnesota and Iowa, where relatively less-traveled U.S. and state highways were predicted to see a large increase. By contrast, roads on the eastern bank of the Mississippi would see less impact because there is a relatively lower amount of tonnage shipped from ports that would use these routes, and relatively higher preexisting truck traffic counts.

Across the region, based on a calculated one-season shutdown, between 9.1 and 12.4 million tons of agricultural goods would be displaced. That’s equivalent to between 367,000 and 489,000 truckloads. It would cost as much as $283 million to move these loads by truck, and damage from these movements could cost states up to $28.8 million.

The researchers point out that they were looking at only a subset of commodities that are shipped on this route; previous studies have shown that the true cost of a river shutdown would be much greater, as it would raise the cost of shipping for multiple commodities and reduce the economic competitiveness of the Upper Midwest.

Armed with the results of this study, state governments, departments of transportation, and port authorities can work together to make data-driven decisions about balancing the costs of maintaining lock and dam infrastructure with the impacts a potential failure would have on other freight transportation modes.