An intoxicated driver loses control of his speeding vehicle. It jumps the curb and collides with a trio of young pedestrians, killing one.

Had a nearby traffic signal and the vehicle itself been equipped with connected vehicle technology capable of transmitting a warning to the pedestrians, perhaps a loud cell phone alert, they might have had time to move to safety.

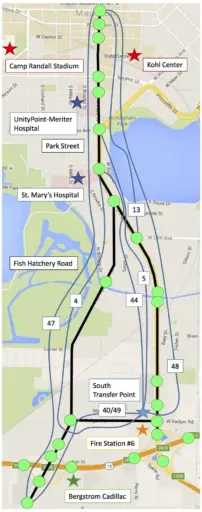

The eventual 6.2-mile corridor will connect the campus with the Beltline Highway. It serves emergency vehicles for two hospitals and a fire station and frequently handles heavy event and bus traffic. Image courtesy of Jon Riehl.

The eventual 6.2-mile corridor will connect the campus with the Beltline Highway. It serves emergency vehicles for two hospitals and a fire station and frequently handles heavy event and bus traffic. Image courtesy of Jon Riehl.

Such technology, which allows vehicles, pedestrians and even our transportation infrastructure to “talk” to each other, is an incremental step on the path to a future that includes fully autonomous vehicles.

And, with researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the city of Madison is now turning heavily traveled Park Street into a testbed for connected vehicle technology—one of only a handful in the United States.

Along the busy 3.0-mile street, which links Madison’s Beltline Highway with the UW-Madison campus, the researchers will install five radio units on traffic signals and at least four in city-owned vehicles that frequently travel the area in early 2018, with plans to expand the testbed to a larger 6.2-mile loop—the Madison connected vehicle corridor—soon.

“This corridor is part of the U.S. Department of Transportation-designated Wisconsin Automated Vehicle (WiscAV) Proving Grounds established in January 2017,” says Jon Riehl, a researcher in the UW-Madison College of Engineering’s Traffic Operations and Safety Laboratory, which is leading the WiscAV effort. “Connected vehicles and autonomous vehicles are separate right now, but half of the nation’s 10 proving grounds are currently pursuing connected vehicle projects because all autonomous vehicles will eventually be connected, as well.”

The backbone of Madison’s corridor—already installed by city engineers in anticipation of future needs—consists of a high-speed fiber network that connects traffic signals and advanced traffic controllers with each other. The new radio units will use dedicated short-range communication (DSRC), an open-source wireless communication protocol that allows only the messages of interest to be transmitted among traffic entities.

Once the units, which were donated by private companies, are installed, city staff and UW-Madison engineering and computer sciences researchers will extensively test the technology and will then develop tools, such as the early-warning system for pedestrians, that will initially focus on safety. In parallel, UW-Madison mechanical engineers will simulate the corridor in a virtual reality environment.

For assistant city traffic engineer Yang Tao, connected vehicle technology is one of several strategies for tackling Madison’s transportation challenges. Photo by Silke Schmidt.

For assistant city traffic engineer Yang Tao, connected vehicle technology is one of several strategies for tackling Madison’s transportation challenges. Photo by Silke Schmidt.

“The city’s goals for this proof-of-concept project are to develop applications that demonstrate the value of connected vehicle technology to the public and will help us obtain federal grants to expand the corridor to more than 20 infrastructure units,” says Yang Tao, Madison’s assistant city traffic engineer. “We want to improve safety and mobility while also promoting equity.”

Given these goals, it’s easy to see why the city chose this particular corridor.

It connects downtown Madison and the campus with the area’s only freeway; it has frequent high-volume event traffic because of its adjacent athletic facilities (UW-Madison’s Kohl Center and Camp Randall Stadium); it includes a public transportation hub and experiences heavy bus traffic, in part because nearby disadvantaged communities rely on public transportation to get to work and school; and it is frequently used by emergency vehicles because two major hospitals and a fire station are located on or near the corridor.

To achieve the city’s mobility and equity goals, Tao ultimately hopes to install onboard units in city buses to improve their arrival-time performance through a signal priority mechanism: When the bus unit’s GPS system detects a substantial delay from its schedule, it can communicate with a connected traffic light unit to allow the bus to catch up while holding back lower-occupancy vehicles.

One of the five radio units that will be installed on Park Street’s traffic signals. Photo by Jon Riehl.

One of the five radio units that will be installed on Park Street’s traffic signals. Photo by Jon Riehl.

For Peter Rafferty, a program manager in the Traffic Operations and Safety Laboratory, the connected vehicle corridor is part of a larger portfolio of WiscAV initiatives that is cementing UW-Madison’s leadership in the field. “We are excited to partner with the city since our ability to conduct real-world tests of connected vehicle systems will greatly benefit our research in the autonomous vehicle area,” he says.

Rafferty serves on Gov. Scott Walker’s recently convened steering committee on connected and autonomous vehicle testing and deployment, as does David Noyce, a transportation expert and UW-Madison professor of civil and environmental engineering who directs the Traffic Operations and Safety Laboratory.

“Wisconsin is quickly becoming a national leader in connected and autonomous vehicle research,” Noyce says. “With a recently established collaboration with Southeast University in Nanjing, China, which houses that country’s top-ranked transportation engineering program, we’ll be able to lead this kind of research on an international scale.”

Tao also hopes to position Madison among the top-10 cities in the country for connected vehicle technology. “This is one of many strategies we are pursuing to tackle Madison’s transportation challenges in the next decade or two,” he says. “Our collaboration with an academic research powerhouse like UW-Madison is key to the project’s success because the public and private sectors need to work together to ensure that this new technology is developed to serve the interests of all members of our society.”