The best-laid plans of many parents are falling apart after weeks of keeping their kids home during the COVID-19 pandemic—and for many families, Netflix binges and video games are replacing any attempts at home schooling.

But University of Wisconsin-Madison engineers have developed a few more options for productive screen time. In recent years, they have collaborated with UW-Madison’s Field Day Lab to create educational—but most importantly, fun—games aimed at middle and high schoolers.

Over the last four years, the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC) at UW-Madison, a National Science Foundation-funded center that supports materials science research and promotes education and public engagement, has created three games focused on materials science.

The first game had its genesis several years ago, when Harvey D. Spangler Professor of Materials Science and Engineering Dane Morgan approached MRSEC about developing a touch-screen game that simulates how atoms form and interact based on the most up-to-date research.

The way most middle-schoolers currently learn about atoms is via diagrams of circles with electrons orbiting them. But Morgan believed that a game in which students could manipulate, transform and understand atoms on a more intuitive level would offer a better introduction.

“We talked about this idea of putting the physics behind a computer simulation so students and teachers could use an app to learn about how atoms move, connect to each other, how they build structures, and the effect of things like temperature and pressure on atomic structure,” says Anne Lynn Gillian-Daniel, MRSEC director of education.

The result, created in deep collaboration with the designers and coders at Field Day, is a game called AtomTouch, a simulation designed for fifth grade through early high school that takes about half an hour to play through. Players can add and subtract atoms from molecules and explore different types of atomic bonds and states of matter.

“There’s experiment, then there’s theory, where you just write down equations, and then there’s simulation where you take the equations and you actually re-create the world virtually on a computer,” says Morgan, an expert in molecular dynamics simulation. “The power of that is extraordinary.”

After testing the game with eighth-graders at Georgia O’Keefe Middle School in Madison, Wisconsin, and fixing a few bugs, Field Day released the game. It was a hit with middle-school teachers who have incorporated it into their lesson plans. The popularity of AtomTouch, and the fun of making it, convinced MRSEC educators that digital games would be a good area of interest for the center.

For their next game, MRSEC educators hoped to share its research about how atoms come together to form crystals. Researchers can manipulate crystals to make materials, like solar cells or computer chips, with certain properties.

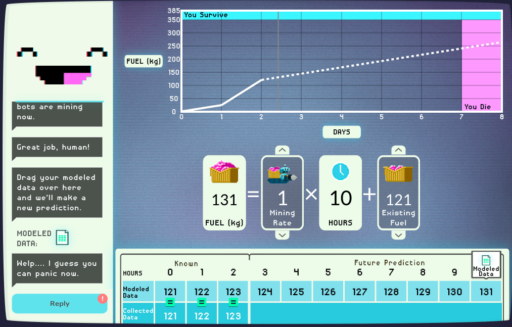

Image from Lost at the Forever Mine, a video game in which players are intergalactic materials scientists who crash land on an abandoned mining planet. Credit: Field Day Lab.

Image from Lost at the Forever Mine, a video game in which players are intergalactic materials scientists who crash land on an abandoned mining planet. Credit: Field Day Lab.

Using theoretical and mathematical modeling based on work by Materials Science and Engineering Professor and MRSEC Interdisciplinary Research Group Co-Leader Paul Evans, Field Day and MRSEC educators developed Crystal Cave. The game is part of a series of games created by Field Day called The Yard which has an overarching narrative featuring kids who hang out in a junkyard and use games to understand concepts that include UW-Madison research about the water cycle, earthquakes, antibiotic resistance and other topics.

In Crystal Cave, kids from The Yard try to grow crystals and build brick walls. Players help out by packing together various shapes of crystal molecules to understand which are the most stable, mimicking the way crystals grow in nature.

MRSEC’s third entry into the world of video games is a space adventure called Lost at the Forever Mine, in which players are intergalactic materials scientists who crash land on an abandoned mining planet. Their goal is to mine and process enough fuel to stay alive and eventually repair the ship. Over the course of the adventure game, which Field Day has dubbed a “math drama,” students must create mathematical models in order to allocate their time and resources. Along the way, there are cute robots that drop by, some very impressive art created by Field Day, as well as MAL, a sassy robot that may or may not be an ally.

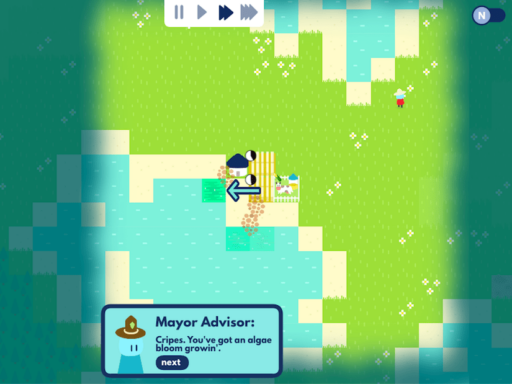

The Lakeland video game teaches students about complex factors that affect lake pollution. Players attempt to grow a town near a lake without degrading the water quality. Credit: Field Day Lab.

The Lakeland video game teaches students about complex factors that affect lake pollution. Players attempt to grow a town near a lake without degrading the water quality. Credit: Field Day Lab.

Matthew Stilwell, assistant director of education for MRSEC, says developing that game was a challenge, but it was worth the effort. “There are a lot of different themes and contexts, and the game went through a lot of iterations and feedback,” he says. “Players are trying to get a basic understanding of real-world phenomena and trying to predict future events from the data they collect.”

Field Day’s most recent engineering-inspired game is Lakeland, based on research conducted by Victor Zavala, the Baldovin-DaPra Associate Professor in chemical and biological engineering. Zavala has researched the ways phosphorous pollution from the dairy industry ends up in lakes and bodies of water, leading to toxic algae blooms that harm fish and the environment and ruin beach days.

Lake pollution is a very complex system, with all sorts of choices by individuals, industry and government combining to improve the problem or make it worse. Zavala wanted to represent that complexity in a game. In Lakeland, aimed at high school students, players start from the beginning, attempting to grow a town near a lake without degrading the water quality. That means correctly placing houses, farms and dairies in places that won’t affect the lake while also judiciously using fertilizer to produce enough corn and milk to export and feed the local population.

While the cute little townspeople make the game fun, keeping them alive and the lakes clean is not a simple task. “Failure is an awesome part of learning,” says Field Day Director David Gagnon. “That’s where the action is. In well-designed video games, you’re failing all the time. And when you do succeed, it matters.”

For Zavala, the game is a great way to introduce complex systems to students, and he says after working with Field Day, he plans to add games to his burgeoning portfolio of public outreach whenever he can.

“The nature of the work that I do is very naturally aligned with games,” says Zavala. “It’s so scalable. You can reach so many people that way.”

For the time being, MRSEC, Zavala and Field Day hope to reach some of the students and parents sitting at home looking for something meaningful to occupy their day. Each game takes 15 to 30 minutes to play and is available for free from Field Day and on the GameUp section of the educational website BrainPOP.