On April 8, 2024, a rare total solar eclipse will take place across North America, affording viewers across several U.S. states at least a partial glimpse of the rare phenomenon.

But don’t look up—at least without the right protection.

We asked Mikhail Kats, the Jack St. Clair Kilby Associate Professor and Antoine-Bascom Associate Professor in electrical and computer engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and an expert in optics and photonics, to help us understand how to best view the celestial event safely.

Why can’t you just look at the eclipse? The sun is mostly blocked by the moon.

The surface of the sun is about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit, which glows brightly in the visible, ultraviolet and infrared spectrums. It is generally not recommended that you stare into the sun with your eyes wide open on a clear day. That can cause physical damage to the retina, which is home to the sensitive cells at the back of your eyes that enable vision, similar to sensors in a camera.

During a sunny day at the beach, our pupils get smaller and let in less light. We also have a biological instinct to look away from the sun, or blink before it causes damage. But during the eclipse, when only a crescent-shaped sliver of the sun is visible, something interesting happens: That blinking reflex is reduced and our pupils open up, simply because less overall light is coming into our eyes. However, the intensity of light coming from the region of sun that remains visible is still the same, and the opportunity for damage is still there. In some cases, people staring into an eclipse have had a crescent shape burned into their retinas.

How do eclipse glasses protect our eyes?

Eclipse glasses are essentially filters you put in front of your eyes that only let a small fraction of the light come through, so it becomes safe. Regular sunglasses reduce light intensity between two and 10 times. The standard for safe eclipse glasses is that they transmit no more than .003% of visible light. That’s reducing the intensity by 30,000 times or more. When you attenuate sunlight by that amount, there’s really no risk.

There are different ways to make the filters in eclipse glasses. Some companies use a polymer infused with black carbon particles, absorbing most of the light, or several alternating layers of polymers to efficiently reflect. In other designs, a polymer film is covered with a very thin layer of metal, often aluminum. Metals reflect almost all the light that falls on them, but when you make metal very thin, it becomes partially transparent. Eclipse filters can be made inexpensively, but they can also be easy to scratch—so when you’re evaluating whether or not eclipse glasses are safe, you should hold them up to the light to see if there are any visible scratches or holes. If there are, you probably shouldn’t use them.

Graphic courtesy of NASA

Graphic courtesy of NASA

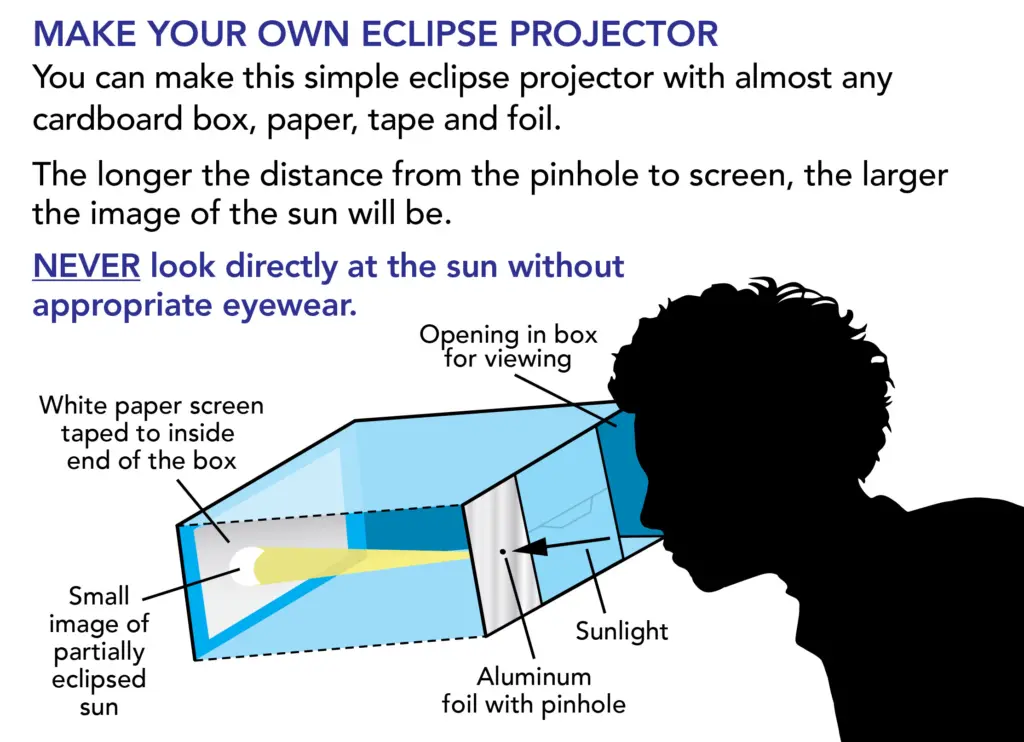

If you don’t have glasses, are there other ways to watch?

There’s this very old, cool concept called a pinhole camera, or “camera obscura,” in Latin. You can just take a shoebox or something similar and poke a hole in it; the light from the sun will project an image on the inside surface of the box. You also can use a piece of paper or cardboard, poke a pinhole in it, and project the image of the sun onto the ground or another piece of paper below it. Any number of ways are fine to look at the eclipse, as long as you’re not putting the full intensity of the sun onto your retinas.

What’s your plan for watching the eclipse?

I’ve never seen a total eclipse, so my wife and I are driving to Muncie, Indiana, to watch it. From what I gather, the odds of clear skies in Indiana are only about 1 in 3—so it’s not great, but we’re going to try.

My intuition as an optics scientist is to try to do some cool measurements: bring along cameras, spectrometers, telescopes, stuff like that. But the advice I’ve gotten from people is the first time you go, just enjoy it and don’t spend all of your time fiddling with equipment settings. So the current plan is to just bring one camera and enjoy the view, rather than doing something super-fancy.

Top photo caption: Mikhail Kats, the Jack St. Clair Kilby Associate Professor and Antoine-Bascom Associate Professor, wears eclipse glasses. Photo by Alex Holloway.