Marion Gilbert Wells has had a long career in the steel industry and wants to support the next generation of materials science & engineering students.

Marion Gilbert Wells has had a long career in the steel industry and wants to support the next generation of materials science & engineering students.

Many of Marion Gilbert Wells’ peers spent their childhoods rewiring the family toaster or building high-tech model rockets. But that wasn’t the case for Wells. “When I’m speaking to young people, I tell them I didn’t wake up one day and say I’m going to be a materials science engineer,” she says.

But once she found that path, it proved to be a great fit for Wells. She was the first African American woman to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in metallurgical engineering (1981) from what is now the UW-Madison Department of Materials Science and Engineering and has gone on to have a long, successful career in the steel industry as a metallurgical engineer, sales and marketing executive as well as the founder of her own growing industry consultancy, Human Asset Management.

To give back to the College of Engineering, specifically the Department of Material Science and Engineering, Wells is an inaugural sponsor of the Strategic Targeted Achievers Recognition (STAR) Scholars program. A matching grant from The Grainger Foundation is also doubling Wells’ scholarship gift. The program’s goal is to attract the nation’s best and brightest students, including candidates from groups underrepresented in engineering, to the UW-Madison campus. That’s something Wells feels passionate about since her journey at UW-Madison started in 1976 with a similar program.

Her father was a chemist who developed haircare products and her mother was a researcher in biology at the University of Chicago. When Marion Gilbert Wells came home from a career counseling day at her high school with plans to become be an art major, her parents asked her to reconsider.

A family friend offered to give Wells a tour of the metallurgical engineering facilities at the Illinois Institute of Technology to see if it sparked any interest. “What he did, which I thought was very smart of him, is put a piece of steel underneath the scanning electron microscope and magnified it like 1,000 times,” she remembers. “If you’re an artsy kind of person, you see the grains blow up, and you go, wow! He said, ‘If you really like this, you should consider majoring in metallurgy.’”

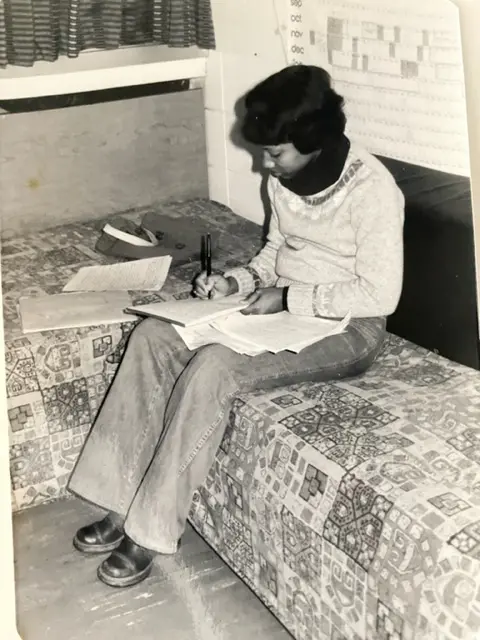

Marion Gilbert Wells studying in her residence hall at UW-Madison in the late 1970s.

Marion Gilbert Wells studying in her residence hall at UW-Madison in the late 1970s.

She did like it, and that path led her to UW-Madison, which offered a pre-engineering program for minorities to prepare them for the College of Engineering. Admission to the college was contingent on successful completion of the requirements of that program. “If you can imagine the summer of ’76, we were always hanging out by Lake Mendota, it was warm and we’re bicycling all over campus,” she says. “I was meeting minority students from all over and it was a first for all of us. It was great. We were enjoying campus life, but also studying hard.”

Wells continued to study hard, graduating in 1981. She then went on to do a year of graduate work at Northwestern University before joining Inland Steel, now part of Cleveland Cliffs in East Chicago, Indiana. “They asked me where I wanted to work, and I said, ‘What is an area with no women?’ They said production. So I said, ‘Okay, sign me up,’” she says.

Wells worked the midnight shift as a supervisor in No. 3 cold mill, a hot and dirty job that served as a great bottom-up introduction to steel processing. After a couple years in the cold mill, she began a string of positions in the company; she worked in the quality division doing technical failure analysis, she served as a technical salesperson in Cleveland, and worked in R&D in Chicago and in 1993 settled in Detroit as a technical salesperson along with her husband.

Wells decided to leave the steel industry in 1996 to focus on her children’s education. She became so involved, in fact, that a former OEM client approached her about preparing his son for college. Wells was intrigued by the offer and realized she was well-suited to coaching students. “I put my engineering hat on and just really started creating a process to get him ready,” she says. Word began to spread about her process, and more parents approached her. “And then I got another student, and another student. So, before you knew it, I was getting paid for coaching, and mentoring students.”

After another brief stint in the steel industry, Wells shifted to a purchasing role, helping a die manufacturer optimize operations and steel buying programs. In 2008 during the recession, Wells had to pivot and partner with a consultancy focused on small to mid-size manufacturers in the tool and die industry, while also coaching students on the weekends. That’s when a student whose parents worked at a press manufacturer asked her a simple, but life-changing question: What you do for students, can you do that for employees? “I was like, oh my goodness, I’ve never thought about that,” she says. In 2012 with the help of family and friends, she launched Human Asset Management with the press manufacturer as their first client.

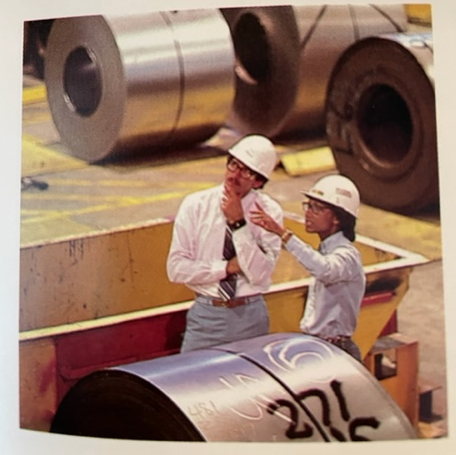

Marion Gilbert Wells worked in many divisions during her years at Inland Steel.

Marion Gilbert Wells worked in many divisions during her years at Inland Steel.

It turned out that, like many companies, that firm was dealing with different generations operating in the same workplace, each with different needs, expectations and work styles. Through her company, Wells has worked for the past decade with major automotive and industrial companies to bridge the gap across generations while improving corporate culture, employee development and other aspects of their businesses.

After years of looking at industrial companies from the inside out, Wells has come to a startling conclusion: Without a major investment in materials education, the industry is facing a crisis. “They don’t know it yet, but there’s going to be a shortage of steel-oriented engineers within the next 10 years,” she says. “The last of the Baby Boomers turn 65 in 2030 and many will be retiring. And due to COVID, for the first time, we have lower enrollments in colleges, leading to gaps in the talent pipeline.”

That’s one reason Wells, who is a member of the MS&E industrial advisory board, is so excited to help fund the STAR Scholars program and is strongly encouraging others to follow suit and take advantage of the matching donation. “I want to use my sales and marketing background and my engineering background to create a call to action to other companies in steel and industry to join us,” she says.

She not only sees this as the right time to raise the profile of materials engineering, it’s also a great opportunity to diversify the field and attract more women and minorities to the industry. While things have changed greatly since Wells worked the night shift in No. 3 cold mill, there’s still a big need to improve diversity in the industry, something she plans to work on more formally in summer 2022 through a research and education project.

“You’ve got a core number of material science and engineering and metallurgical engineering careers that need to be filled with undergraduate students,” she says. “So how do you get the message out? How do you educate the industry on what’s coming? We’ve got to do a better job of attracting students to our industry, and I’m hoping to be able to make a difference based on the experiences that I have had.”

That’s also why Wells is asking UW-Madison materials science and engineering and metallurgical engineering alumni, other College of Engineering alums and industry sponsors to join her in supporting the STAR Scholars program. It’s time, she says, to get a new generation excited about materials, which will continue to be a vital part of our state and national economies.

Make a gift to support STAR scholars through Gilbert-Wells’s fund.

For more information on getting involved with the STAR Scholars program, please contact Scott Simons at the University of Wisconsin Foundation by email at scott.simons@supportuw.org or phone at (608) 308-5235.