As NASA plans crewed surface missions to the Moon and eventually Mars, researchers say managing cognitive fatigue may be essential for safe, effective deep space exploration.

As NASA prepares to send astronauts back to the Moon under its Artemis campaign — and eventually onward to Mars — crews will spend long hours working outside their spacecraft on planetary surfaces. These extravehicular activities, or EVAs, are physically demanding. But they are also mentally demanding in ways that can quietly undermine safety.

Future lunar surface missions will involve longer excursions in partial gravity, higher operational tempo and greater autonomy. While the physical challenges of spacewalks on the Moon’s harsh environment were well documented in the Apollo era, it is less clear how the cognitive demands of specific surface EVA tasks shape crew performance, safety and mission outcomes.

New research published in Frontiers in Psychology suggests that sustaining crew performance during lunar exploration depends not only on physical endurance, but on how effectively mission systems account for cognitive workload — the mental effort required to manage information, maintain situational awareness and make decisions under pressure.

“Artemis missions will require astronauts to manage more complex tasks, for longer periods, with fewer opportunities for real-time support from Earth,” said senior author Dr. Daniel Buckland, an associate professor in the Departments of Emergency Medicine and Mechanical Engineering at UW–Madison and a former deputy human system risk manager for human spaceflight at NASA.

Dr. Daniel Buckland

Dr. Daniel Buckland

“Understanding how cognitive workload affects performance is essential as we move from short ‘fly-by’ excursions to sustained operations on the lunar surface.”

Testing the brain under pressure

The study examined how increasing the cognitive difficulty of EVA tasks affects performance during simulated lunar surface exploration, identifying cognitive workload as a distinct and measurable factor in EVA performance.

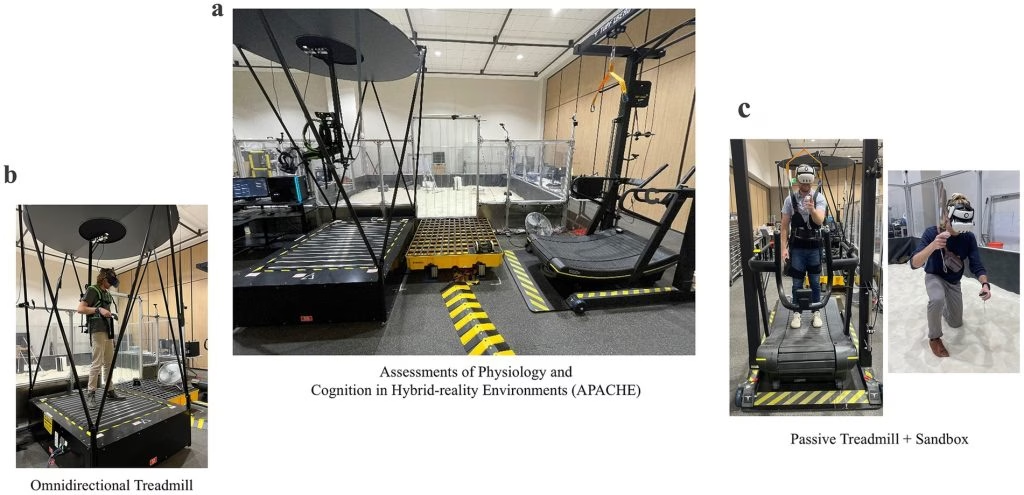

Researchers recruited 14 participants to complete ground-based surface EVA simulations using virtual reality, integrated treadmills and terrain-like sandbox. Cognitive workload was manipulated by varying the difficulty of a geological sampling task — a core activity astronauts will perform during the Artemis III mission — while physical workload was held constant.

Participants completed three concurrent tasks: identifying rock samples, monitoring simulated spacesuit temperature and watching for unexpected discoveries in the terrain. Tasks requiring specialized expertise, such as distinguishing subtle geological features, can be especially demanding for individuals without extensive training — an important consideration as NASA emphasizes a broadly skilled, multidisciplinary astronaut corps, according to Buckland.

(a) Assessments of Physiology and Cognition in Hybrid-reality Environments (APACHE) simulation space at NASA Johnson Space Center; (b) Omnidirectional treadmill; (c) Passive treadmill and sandbox configuration.

(a) Assessments of Physiology and Cognition in Hybrid-reality Environments (APACHE) simulation space at NASA Johnson Space Center; (b) Omnidirectional treadmill; (c) Passive treadmill and sandbox configuration.

Across the simulations, researchers measured subjective workload, working memory performance, physiological indicators such as heart rate, and how effectively participants completed mission-critical tasks.

When cognitive workload increased, participants reported greater mental strain, showed declines in working memory and exhibited physiological stress responses. Performance also suffered: geological sampling became less efficient and accurate, even though participants were physically capable of continuing.

In short, harder thinking — not harder movement — was enough to degrade performance.

Rethinking risk mitigation

Although the study focused on short-term performance, its tightly controlled design allowed researchers to isolate cognitive workload as a distinct risk factor.

For decades, risk during partial-gravity surface exploration has been framed largely as a physical and engineering challenge: individual stamina, conditioning and suit design, Buckland said. The new findings suggest that framing is incomplete.

As NASA plans the next era of human space exploration, the study supports efforts to incorporate cognitive workload considerations into EVA task design, scheduling and performance monitoring, alongside traditional physical risk assessments, according to Buckland.

“Our goal is to predict which tasks, or amount of tasks, are mentally harder than others, and if we can use physiological signals to monitor whether an astronaut is operation in a high fatigue state and likely to miss some aspects of the geography or more likely to make errors,” he said.

Parallels to emergency medicine — on Earth and in space

Buckland said that studying these challenges in space may also inform high-performance fields on Earth by helping scientists better measure, predict and design systems around cognitive fatigue.

“The principles of our study translate directly to emergency medicine, where health care teams routinely make high-stakes decisions in dynamic, unpredictable environments,” said Buckland, an emergency physician with UW Health.

Emergency departments operate continuously, requiring clinicians to maintain situational awareness across multiple patients, technologies and interruptions while responding to rapidly changing conditions — often while working long hours on a 24/7 schedule. Patient-safety research has shown that performance is shaped not only by individual expertise, but by how well systems support working memory and decision-making in these settings.

That same dynamic appeared in the lunar EVA simulations. As cognitive demands increased, performance declined despite unchanged physical effort. Reducing unnecessary cognitive burden and supporting decision-making, he said, may help sustain individual performance in both emergency care and space exploration — environments where small mistakes can carry outsized consequences.

Those insights are increasingly relevant as acute care becomes a more prominent concern in crewed space exploration. Recent medical evacuations from the International Space Station highlight how medical risk grows more complex as human presence in low-Earth orbit and beyond expands.

“As more people spend time in space, including on commercial missions, the need to manage acute medical events becomes more real,” Buckland said. “In those moments, crews may need to make high-consequence decisions autonomously under significant cognitive strain.”

Next, Buckland aims to test the team’s findings in more realistic training and simulation environments that better match conditions on the Moon, and to eventually see if the results are replicated in emergency medicine providers. If the results hold, the challenge will be figuring out how to reduce the impact — either by limiting how many mentally demanding tasks astronauts are asked to complete during a single spacewalk or by designing tools and systems that make those tasks easier to manage.

This project was supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Mars Campaign Office (MCO). The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of NASA.

A version of this story was originally published by the UW-Madison BerbeeWalsh Department of Emergency Medicine.