While countless people around the world grapple with the transition to online learning and remote work in the face of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, a group of University of Wisconsin-Madison engineers is already well-acquainted with the process.

Four Civil and Environmental Engineering students—Thomas Schwarz, Mek Sudhiwana, Mina Naguib and Ebrahim Eldamnhoury—are participating in Architecture/Engineering/Construction Global Teamwork, a course developed and offered by Dr. Renate Fruchter since 1993, in the Project-Based Learning Lab (PBL Lab) in the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department at Stanford University in collaboration with universities and industry partners, which attracts students and mentors from around the world.

During the program, students are split into teams that each must design a theoretical building at different locations around the world. There are challenges along the way—for instance, the teams are judged on matters such as their work processes and building resilience—and the course culminates with presentations about their projects.

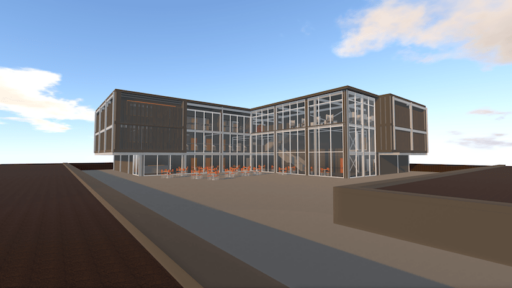

While taking the Global Teamwork course, teams must conceive, plan and design buildings. This rendering shows a design for a theoretical building at the University of California Los Angeles.

While taking the Global Teamwork course, teams must conceive, plan and design buildings. This rendering shows a design for a theoretical building at the University of California Los Angeles.

“All teams are given the same building to conceive, design, plan, and organize,” says John Nelson, a civil and environmental engineering professor of practice and faculty advisor at UW-Madison for the program. “Each team works on a different geographical location, one of which is UW-Madison.”

The teams meet remotely using a variety of digital means including the videoconferencing platform Zoom, which means the program was already equipped for remote education before the COVID-19 pandemic occurred. Nelson says the remote meetings also give the teams a chance to learn by engaging in the type of interactions they’ll face in the working world.

“This gives our students opportunities to participate in global, digital teams, not unlike what happens in practice,” Nelson says. “It’s a pretty high-octane dose of reality to get them ready to go out into the world and practice. It’s one of the best opportunities to experience what it’s going to be like in the real world.”

UW-Madison’s students are on different teams. Schwarz is on a team designing a building for the University of California Los Angeles; Sudhiwana’s team is designing for San Francisco State University; Eldamnhoury’s team for UW-Madison; and Naguib’s team for Bauhaus University in Weimar, Germany.

Each of the projects shares similar challenges; Sudhiwana says, for instance, that the buildings all have very small footprints, which teams must account for not only in designing the facilities themselves but in organizing their construction sites.

Other challenges are location-dependent. Naguib’s team must construct its building at a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which introduces stringent guidelines for the site’s preservation. Eldamnhoury’s team is designing a theoretical building adjacent to the Water Science and Engineering Laboratory at UW-Madison and must consider ways to minimize its environmental impact on adjacent Lake Mendota. Schwarz’s and Sudhiwana’s projects are situated in earthquake zones, which forces the teams to consider designs that can withstand the threat.

“We’re aiming to have our building remain operational after an earthquake without shutting down,” Sudhiwana says. “That’s different from what’s normal when you design a building. We’re trying to go the extra mile there and are exploring different systems to help us do it.”

Teams confer regularly with program alums who act as project “owners” for feedback throughout the program. “This is one of the key points in the project because now we can actually learn how to do a real client-management relationship,” Eldamnhoury says. “They’re not paying in reality, of course, but it’s a simulation and adds an element that I haven’t had before.”

They also seek mentorship from practicing professionals, which they use to modify and refine the building designs. And because the teams are comprised of people from a variety of disciplines, the program gives students valuable exposure to ideas from other fields and experience working with others.

“There’s a lot of cross-disciplinary work,” Schwarz says. “We’re not just working with a team of engineers. It’s structural and MEP engineers, architects, life cycle experts, construction managers, and more. It’s much more representative of the real-world industry and not just working on a team of people from your discipline.”

Because Stanford sits in the heart of Silicon Valley, the teams often get a glimpse at technology before it rolls out for widespread use. For example, Nelson says, the teams were early adopters of Zoom—which has recently surged into prominence as people around the world shift to telecommuting to slow the spread of COVID-19.

“One year, we experimented with robots like Wall-E on top of a Segway,” he says. “They are controlled remotely to circulate in classrooms – one could see students’ work from anywhere in the world. This year is the first year of full-on augmented reality, and the teams use goggles regularly.”

UW-Madison has taken part in the AEC Global Teamwork program since about 2005, Nelson says. Its students have a long track record of success, especially when bringing CEE’s history as a leader in the construction field to bear.

“Our students are often construction managers because we have a world-class construction management program led by Professor Awad Hanna and because 40 percent of our civil and environmental engineering undergrad students study construction,” Nelson says.