In 2022, a team of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, recorded real-time movies of extremely tiny nanocatalysts undergoing dramatic changes during carbon dioxide reduction reactions, which are an important step in making sustainable liquid fuels for fuel cells.

Now, in collaboration with University of Wisconsin-Madison chemical engineer Manos Mavrikakis, they’ve published both theoretical and experimental details for why those changes happened. The researchers described their findings in the June 25, 2025, issue of the journal Nature Catalysis.

Simply, a catalyst is a substance that enables a chemical reaction to happen on its surface more quickly without actually changing itself. Catalysts play a huge role in manufacturing: It’s estimated that 90% of all consumer products involve at least one catalytic reaction in their production, from jet fuel to margarine.

In research, most mainstream models of catalytic reactions assume that the catalysts themselves maintain rigid, unchanging surfaces during those reactions. So when the Berkeley researchers noticed molecules moving and evolving on the surface of the nanocatalyst, they were surprised.

The team—led by Peidong Yang, a professor of chemistry at UC Berkeley, and Miller postdoctoral fellow Yao Yang, now an assistant professor at Cornell University—reached out to their long-term collaborator Mavrikakis and Marc Figueras-Valls, a postdoctoral scholar at UW-Madison, to better understand the evolution of the mobile molecules they recorded.

Marc Figueras-Valls

Marc Figueras-Valls

It turned out that Mavrikakis, an expert in computational chemistry, was looking into similar phenomena. In April 2023, he published a breakthrough paper in the journal Science exploring catalytic reactions on the atomic scale, including models of the movement and evolution of nanocatalysts similar to those the Berkeley researchers believed they had recorded. The Berkeley experimentalists and UW-Madison theoretical team joined forces resulting in a two-year study of copper nanocubes as a model system to explore this emerging model of catalysis.

Recording the actions of nanocatalysts, which can be 10,000 to 100,000 times thinner than the width of a human hair, was an incredibly difficult task, and required the resources and expertise of researchers across several institutions. Using a technique called operando transmission electron microscopy, the Berkeley and Cornell teams recorded real-time videos of the copper nanocubes undergoing transformations.

Those recordings created huge multiple-terabyte datasets, making manual processing impossible. Collaborator Yimo Han, an assistant professor at Rice University, and her group applied a machine learning-based automated algorithm technique designed for four-dimensional electron microscopy to analyze the video data. The algorithm pulled out subtle structural differences of the changing copper catalyst—beyond the normal imaging capabilities of an electron microscope—giving the team an even more detailed look at the process.

They also located copper carbonyl, a molecule predicted by Mavrikakis’ model that is unusually difficult to detect. Using a technique called Raman spectroscopy, collaborator Zhu Chen, an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, and his group extracted signatures of the molecule from the data, confirming that the theory and experimental evidence were converging.

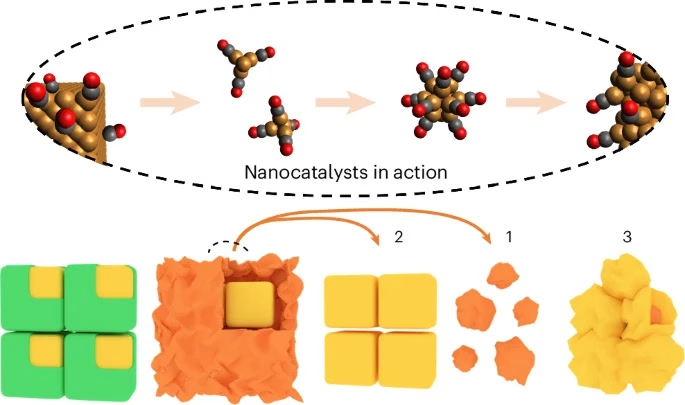

Ultimately, after analysis, the team found that a lot was going on at the nanoscale: During the carbon dioxide reduction reaction catalyzed by the copper nanocubes, carbon dioxide becomes carbon monoxide. The carbon monoxide then interacts with the copper nanocubes, creating the molecule copper carbonyl while other copper atoms migrate and reform into amorphous copper clusters and copper nanograins, which facilitate the catalytic reaction.

All of that was a good thing: The team used the newfound understanding of the evolution process to fine-tune catalysis. For instance, the researchers found differences in the end product depending on the starting size of the copper nanocubes. They also found that techniques like adding oxide coatings to the nanocubes can affect their evolution.

Armed with the blueprint of this model reaction and these new imaging and analytical techniques, the team can now use similar methods and theories to discover or design other nanocatalysts that could improve sustainable production of chemicals, including fuel for fuel cells, green hydrogen and ammonia for fertilizers.

Manos Mavrikakis is the Ernest Micek Distinguished Chair, James A. Dumesic Professor and Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professor in chemical and biological engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Other UW-Madison authors include Michael Rebarchik and Lang Xu.

Other authors include Cheng Wang, Miquel Salmeron, Chubai Chen, Maria Fonseca Guzman, Zhengxing Peng, Yu Shan, Geonhui Lee, Jianbo Jin, Nathan Soland from the University of California, Berkeley, and Lawrence Berkeley National Lab; Chris Pollock, Shikai Liu and Valentin Briega-Martos from Cornell University; Chuqiao Shi from Rice University; and Yves Murhabazi Maombi and Pulkit Jain from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

The work at UW-Madison was supported by Department of Energy (DOE) grant FG02-05ER15731 and DOE Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 using NERSC award BES-ERCAP0032205; and by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division of the US Department of Energy under contract DE-AC02-05CH11231, FWP CH030201 (Catalysis Research Program).