Soren Goldsmith knows most people don’t think about salt marshes that often—but with the help of an innovative amphibious enclosed camera, he’s creating connections to those lands through photos of the wildlife that live in these unique environments.

A rising junior studying geological engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Goldsmith spent much of the 2024-25 academic year working to invent the system, which is meant to survive long deployments in salt marsh tidal zones to capture underwater wildlife. Goldsmith had help on the project from junior mechanical engineering student Ethan Arterburn and group members from Engineers for a Sustainable World.

“Tidal marshes are really dynamic, scientifically important places,” says Steven Loheide, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at UW-Madison and Goldsmith’s advisor for the project. “They’re changing so fast due to changing weather regimes and changing sea levels pushing the boundary of marine life and terrestrial life further inland. So how do these ecosystems adapt to that? What Soren has done is built something that can help monitor those changes and hopefully get people, and himself, more excited about that.”

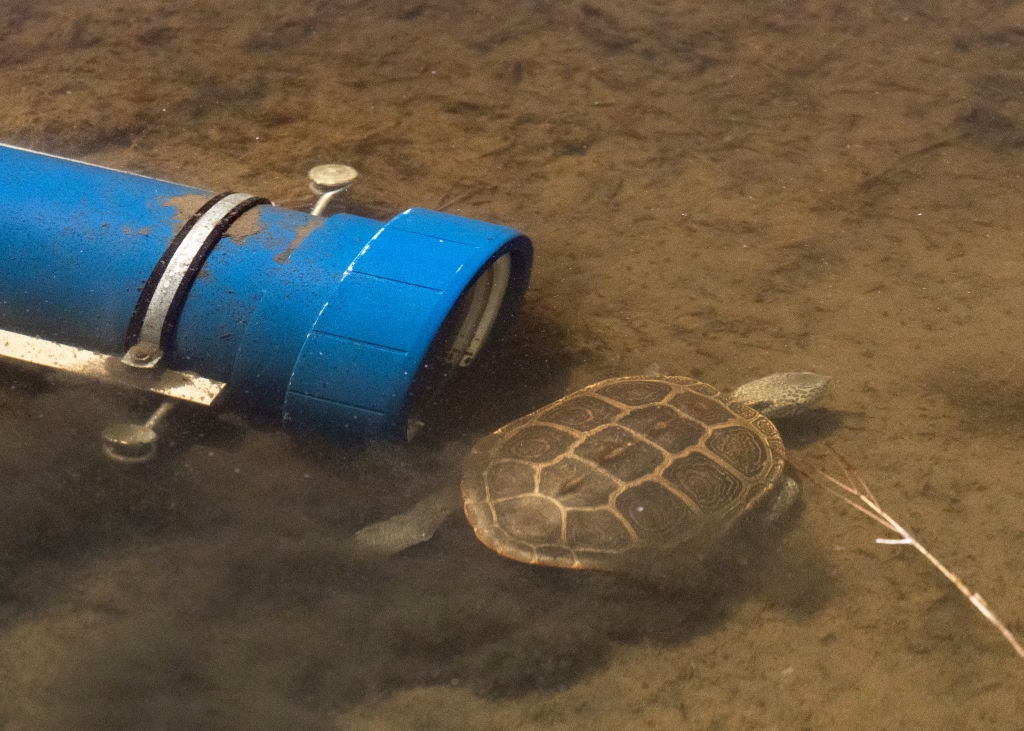

The system consists of a DSLR camera, a small computer, and batteries inside a sealed PVC pipe with a dome port at the camera-facing end. The camera uses customized motion-sensing software to analyze what it “sees” and then snap pictures of aquatic wildlife. It is, to Goldsmith’s knowledge, the first system of its type, and has already been deployed several times since May 2025, capturing stunning pictures of fish, crabs and turtles.

The National Geographic Society supported Goldsmith’s work through its Young Explorers program.

Goldsmith is from Lexington, Massachusetts, and his project proposal focused on New England’s salt marshes. These coastal grasslands regularly flood and drain as the tides push seawater in and out.

He specifically wanted to photograph the diamondback terrapin, a turtle species that lives in salt marshes along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. The diamondback terrapin is classified as a vulnerable species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature; it’s a threatened species in Massachusetts under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

A diamondback terrapin swims in front of the submerged tidal camera. Photo by Russell Laman/National Geographic.

A diamondback terrapin swims in front of the submerged tidal camera. Photo by Russell Laman/National Geographic.

“They’re these iconic turtles that are really important to salt marshes,” Goldsmith says. “But it’s almost impossible to get good imagery of their behavior underwater because they’re really skittish. I needed to be able to get photos close to them, but I couldn’t do that by hand. This is part of my effort to raise awareness about the salt marshes and some of the troubles they’re facing due to climate change and development. I thought if I could tell a story through these turtles, it could get people more interested. It’s hard to get people emotionally invested in just land, but it’s easier to connect when there’s an animal they can see.”

Goldsmith, who has a background in wildlife photography, says that developing his camera was trickier than it might seem. He quickly learned there’s no suitable underwater equivalent to trapping, or trail, cameras used on land to track wildlife presence and movement in an area.

“Traditional land camera trapping uses infrared sensors, which are heat-based,” he says. “So you set the camera up, and it will detect the body heat of a coyote passing by and take a picture. If you take that sensor and put it underwater, it doesn’t work anymore.”

With infrared sensors out of the picture, Goldsmith turned to a few other options. First, he set up a camera that took pictures every few seconds. But that didn’t work well, because the constant photo-taking chewed through the camera’s battery and was prone to taking pictures of nothing at all. So he scrapped that idea.

He also tried using a GoPro with motion-detecting software. That got closer, but didn’t allow him to control the software in the way he needed, and the camera’s optical system didn’t suit the task.

So, like any engineer faced with a challenge, Goldsmith decided to build his own. Working with his team, he designed both the enclosure and the software that powers the camera when it’s left in the marsh for up to two weeks at a time.

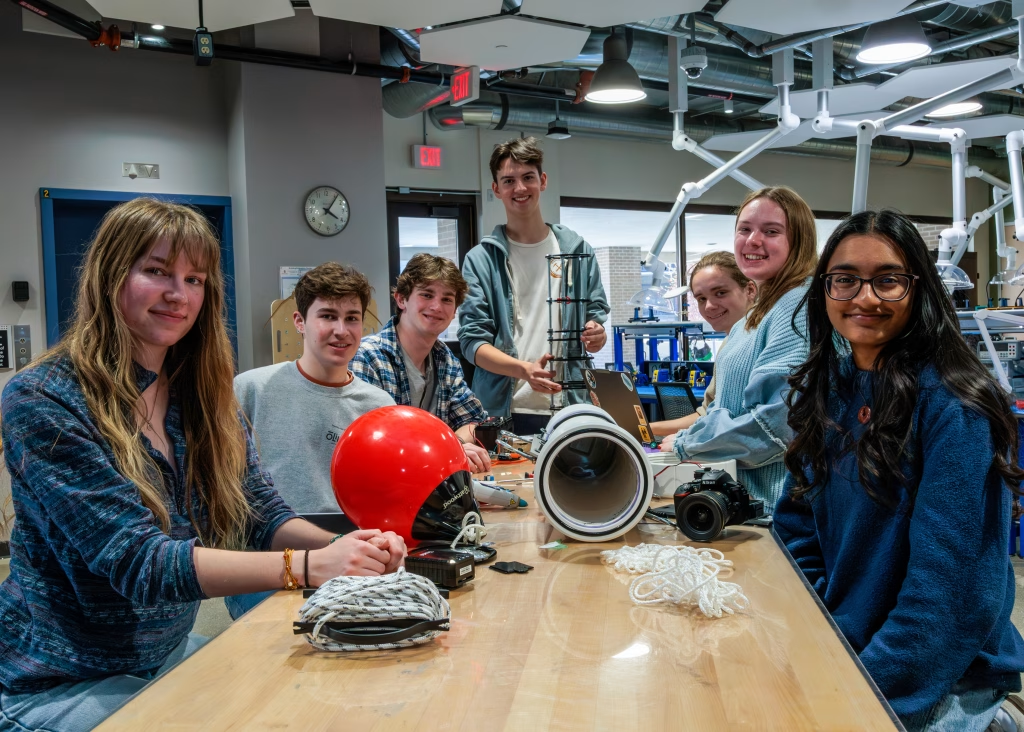

It was, Goldsmith says, a lot of coding and soldering, and learning skills that fall outside the traditional lines of his geological engineering discipline. The team spent a lot of time using the College of Engineering Design Innovation Labs (makerspaces), the availability of which, Goldsmith says, made the project much easier.

The Engineers for a Sustainable World team works on the tidal camera in the Grainger Engineering Design Innovation Lab in Wendt. Pictured, from left, are Lily Vasser, Ryan Sinnreich, Ethan Arterburn, Soren Goldsmith, Donovan O’Connor, Teagan Strecker and Ananya Shankar. Photo by Russell Laman/National Geographic.

The Engineers for a Sustainable World team works on the tidal camera in the Grainger Engineering Design Innovation Lab in Wendt. Pictured, from left, are Lily Vasser, Ryan Sinnreich, Ethan Arterburn, Soren Goldsmith, Donovan O’Connor, Teagan Strecker and Ananya Shankar. Photo by Russell Laman/National Geographic.

Throughout the project, they also had to account for the environment they were building and testing in—Madison’s Lake Mendota in the middle of a frigid Wisconsin winter—versus the warmer tidal environment the camera would ultimately deploy to.Sometimes, for example, that included figuring out if moisture inside the enclosure after a test was because of a leak or a result of condensation that formed when a warm camera system plunged into cold water.

That, says Loheide, was yet another opportunity to learn and to problem-solve. “It was a fun experience watching Soren go through this, trying to deploy and build this here in Madison in the winter, knowing that he’s going to deploy it in a very different environment,” Loheide says. “That’s in a tidal environment with salt water instead of fresh water and in much warmer water. Every time you deploy in a different environment there will always be new design challenges to consider.”

As the project wrapped up in summer 2025, Goldsmith says he and his team recognized that their camera could have a huge range of uses. “What we’ve realized as we’ve talked to people is that the technology in this system is something that could be extremely impactful both for photographers and to researchers,” Goldsmith says. “There are a lot of other scientists I’ve talked to who are very interested, so one thing we’re starting to look at is how we can make it more of a formal research tool and what it takes to do that.”

As he looks ahead to the rest of his time at UW-Madison and beyond, Goldsmith says he wants to keep working to improve the camera. He says the hands-on learning project has also given him a new appreciation for how engineering and understanding the world around us intersect.

“I know I want to keep doing engineering and building equipment,” he says. “I like the idea of building something that other people can use to help them see something they’ve never seen before, and how it connects to exploration and using these tools to understand more about the world around us.”

Featured image caption: Soren Goldsmith checks on his camera in the field in Massachusetts. Goldsmith designed the camera, with support from the National Geographic Society, for long deployments in New England tidal marshes. Photo by Russell Laman/National Geographic.