How did life on Earth originate? Could a bombardment of comets and asteroids laden with water, ice and essential organic molecules have enabled emergence of life on our planet early in its history? To explore this possibility—and to simply better understand comets more broadly—NASA is considering a mission that could return samples from a comet to Earth in the year 2038. If the mission is greenlighted in 2019, its approval will be in part thanks to a unique and informal collaboration between two old University of Wisconsin-Madison classmates and a group of enterprising and enthusiastic students at UW-Madison and UW-Platteville.

NASA scientist and UW-Madison MS&E alumnus Todd King (right) takes measurements of the completed comet sample return capsule prototype in the MS&E foundry. Photo by Kyle Metzloff.

NASA scientist and UW-Madison MS&E alumnus Todd King (right) takes measurements of the completed comet sample return capsule prototype in the MS&E foundry. Photo by Kyle Metzloff.The collaboration began soon after NASA scientist Todd King, who is a 1996 graduate of UW-Madison’s materials science and engineering PhD program, became involved in the comet proposal—known as Comet Astrobiology Exploration Sample Return, or CAESAR. King is an experienced spaceflight instrument manager, and he has worked on a number of NASA missions in recent decades, including the James Webb telescope, which will replace Hubble, and missions aimed at understanding the atmospheres and environments of Mars and the Moon. His work on the Mars mission led to King being tapped to manage the development of the potential CAESAR mission’s camera suite. But in the early stages of a NASA mission proposal, when it was vying for approval among as many as a dozen or so potential missions, King says that formal roles often take a backseat to informal problem-solving. “Everyone does a little bit of everything during the proposal development phase,” King says.

And the most crucial element of the mission proposal to nail down was establishing that it would be possible to safely return a comet sample to Earth’s surface for study.

“CAESAR is all about getting a sample from a comet nucleus back to Earth,” King says. “One of the biggest challenges in the initial proposal was that we had to come up with a design to show that, once we grab and store a sample, we can in fact bring it back to Earth, re-enter Earth’s atmosphere, and land on the ground still intact and keep it cold long enough for transport to a lab. It has to survive a hot reentry and hard landing.”

The group, led by Steve Squyres of Cornell University and Dave Mitchell at NASA, wanted to beef up its proposal beyond computer models and demonstrate with a physical prototype that the feat would be possible. They needed something with roughly the same shape and mass as the proposed return capsule that they could drop in a portion of the Utah desert with uncommonly soft soils where the actual return capsule would land in 2038. In his search for an appropriate stand-in, King initially cast a wide net.

“I called a whole bunch of places that I thought would maybe have something about the right mass,” King says. This included calls to several wrecking ball companies. “I thought that wrecking balls might be roughly the right shape and mass, but none of the companies had anything small enough for us.”

And then King got to thinking about his time in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at UW-Madison.

Kyle Metzloff, UW-Madison MS&E alumnus and UW-Platteville professor of industrial studies, prepares the mold for the casting of the comet sample return capsule prototype for NASA’s proposed CAESAR mission. Photo by Greg Johnson.

Kyle Metzloff, UW-Madison MS&E alumnus and UW-Platteville professor of industrial studies, prepares the mold for the casting of the comet sample return capsule prototype for NASA’s proposed CAESAR mission. Photo by Greg Johnson.“I remembered that Madison had a small-scale working foundry when I was there in the ‘90s, and I reconnected with a classmate who I knew worked in the foundry and would be able to tell me if what we needed could be made there,” King says.

That former classmate, Kyle Metzloff, just so happens to be on the faculty at UW-Platteville and also had recently taught UW-Madison’s first metal casting course in nearly 20 years. The foundry, located on the first floor of the Materials Science and Engineering Building, was used every so often by an engineering student organization. Metzloff was already making improvements—and seeking support for even more—when King got in touch

with him in October 2016. The timing was perfect.

“I told Kyle what we needed, roughly, and asked him if that was something they could do,” says King. “He said, ‘Yeah, sure we can do that.’”

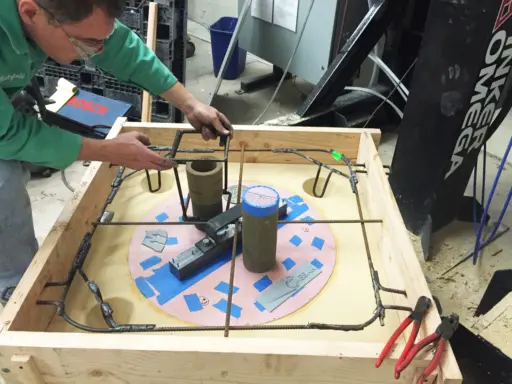

And so began a flurry of activity orchestrated by Metzloff, who above all wanted the project to provide a challenging and exciting learning opportunity for students. King sent Metzloff requirements for the prototype’s design, which Metzloff used as the basis for a design challenge for his students in Platteville. After hundreds of hours refining the design for the sample return capsule, Metzloff’s Platteville students produced a workable pattern that fit within the constraints set by the CAESAR team.

At the same time, with the support of funding by industry partners who wanted to see the foundry up and running once again, Metzloff and a team of students in Madison made preparations for the pour. They had to purchase several pieces of equipment, including a used sand mixer and a new lining for the foundry’s largest furnace, which with some ingenuity and some modifying was just large enough to handle the task of casting the prototype.

Todd King inspects the completed comet sample return capsule prototype in the MS&E foundry. Photo by Kyle Metzloff.

Todd King inspects the completed comet sample return capsule prototype in the MS&E foundry. Photo by Kyle Metzloff.“Students helped out in every aspect of this project,” Metzloff says. “Especially as we prepared for molding the sand and casting the iron, the students in Madison really stepped up and put in long hours to see this through.”

Among those students was Greg Johnson, who at the time was wrapping up his undergraduate degree in materials science and engineering. Johnson is currently working toward a master’s degree in the department. He and his peers, with Metzloff’s guidance, worked through the night in the days leading up to the pour to prepare the foundry and build the mold, which weighed 2,000 pounds and required a small crane to maneuver into place.

And the students did this all simply out of enthusiasm for the casting process and the exceptional experience of assisting a potential NASA mission—it was a purely extracurricular choice.

“And it was a jumpstart to get this place to where it is today,” says Johnson, giving a tour of the foundry in early 2018. Johnson, who is planning for a future in the metals or ceramics industries, took Metzloff’s initial metal casting course as an undergrad and became spellbound by the processes he was able to witness firsthand in the foundry.

“It’s a fascinating experience working in here because from almost any class you take in materials science and engineering, you can apply something from it here,” Johnson says. “There’s phase transformations, thermodynamics, deformations, heat, fluid and mass transport; the furnaces work via electronic interactions; you can get everything out of the macro and microprocessing classes. It’s all in here, it’s all applied, and it’s inspiring to see what you’re learning in action.”

A final frenzy of preparation preceded the December 2016 arrival of King and Squyres, who flew into Wisconsin to witness the drama of the casting and give talks to students. The hard work paid off, as the casting produced exactly the prototype NASA was after.

Kyle Metzloff led the Wisconsin collaboration with NASA. Here, Metzloff works on the sample return prototype after casting. Photo by Greg Johnson.

Kyle Metzloff led the Wisconsin collaboration with NASA. Here, Metzloff works on the sample return prototype after casting. Photo by Greg Johnson.“They nailed it,” King says. “Kyle’s teams at Platteville and Madison did a fantastic job for us and all on schedule. Even at the proposal phase, at NASA staying on schedule is everything.”

The collaboration paid off: on December 20, 2017, NASA announced that the CAESAR project is one of two finalists among a dozen initial proposals as the fourth installment of its New Frontiers program, which has already sent probes to Pluto and Jupiter, with another one on its way to pick up and return a sample from an asteroid. The CAESAR mission is up against some stiff competition; the other finalist is a proposal to send a probe to Saturn’s moon Titan, which is another high-priority target for NASA as it seeks to understand the origins of life on Earth.

Still, the CAESAR proposal is strong, King says, in no small way because of the contributions of Metzloff’s teams in Wisconsin. The CAESAR proposal hopes to return a sample from the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko—the same comet that the European Space Agency successfully explored with the Rosetta spacecraft and Philae lander. The Rosetta mission provided exciting confirmation that the comet is rich in some of the building blocks of life, including essential amino acids and phosphorus. The next crucial step in understanding the comet is to bring samples home, King says.

“Now, as we move to the next phase, we’re looking to strengthen our proposal even more,” King says. “We strongly believe that we have a very implementable, low-risk concept, and we’re excited for the opportunity to move CAESAR forward under the New Frontiers program. The strength of this proposal was possible only with the Wisconsin contribution of this key component.” NASA expects to decide which mission will be greenlighted in summer 2019.

Collaborating with NASA to bring back material from a comet