The magnetic soft robots in Yunus Alapan’s lab on the third floor of the Mechanical Engineering Building on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus don’t look like complex miniature droids or anything you’d find in a science-fiction story.

In fact, they look more like tiny slabs of chewing gum, fresh out of the wrapper. But then, with a team of mechanical engineers tinkering on their design, there’s much more than meets the eye. Once they’re placed in water and controlled with a magnet, they come alive.

The soft, elastic strips of silicone polymer—about the length and width of a capsule pill, but rectangular and much thinner—are infused with magnetic particles that allow them to move with the help of wireless magnetic signals.

“You can actually bend them to walk, you can roll them, you can make them jump and crawl within narrow tubes,” says Alapan, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering who joined the UW-Madison faculty in spring 2024.

The soft robots can also carry cargo, which makes them potentially useful for delivering drugs with precision, hunting target cells, and more in the GI tract and other passages and crevices within the body.

But loading cargo while maintaining freedom of movement is tricky; some research teams’ designs result in limited locomotion, while others are prohibitively complicated.

Alapan’s lab has developed a solution that involves turning the whole material into a cargo carrier. By planting interconnected pores throughout the material—with the exception of the bottom—and sealing the top with wax, his group has created a design that preserves flexibility for movement while enabling liquid cargo release at different magnetic field strengths.

To create the pores, the researchers turned to a kitchen staple. They sprinkled both coarse and fine sugar particles into the matrix; the sugar later dissolves to leave gaps. A thin sheet of wax seals the top, holding in the cargo, even in a liquid environment.

“We want to locally release the liquid cargo,” says Youyi Zhou, a second-year PhD student in Alapan’s lab. “So how to design a seal for this structure is very important.”

Under a low magnetic field, the strips can still deform—and, thus, move—without breaking the seal; Alapan’s team found the wax didn’t break until the strength of the magnetic field increased to 70 milliTesla, even after hours of controlled locomotion in an aquatic environment. That pattern of movement and then release could be applicable for, say, maneuvering through a patient’s GI tract and then delivering an antibiotic to a targeted site.

A paper detailing their design and showcasing the material’s performance earned Alapan and PhD students Zhou and Fatih Kocabas the Best Application Paper Award at the International Conference on Manipulation, Automation and Robotics at Small Scales held at Purdue University in summer 2025.

Moving forward, the lab is exploring multi-cargo, sequential delivery. The group is pursuing additional funding from federal funding agencies to support that work, which will require a more complex deformation system and continued design refinements.

“It’s all a bunch of trade-offs, right?” says Alapan. “So that’s why it’s a very good engineering project.”

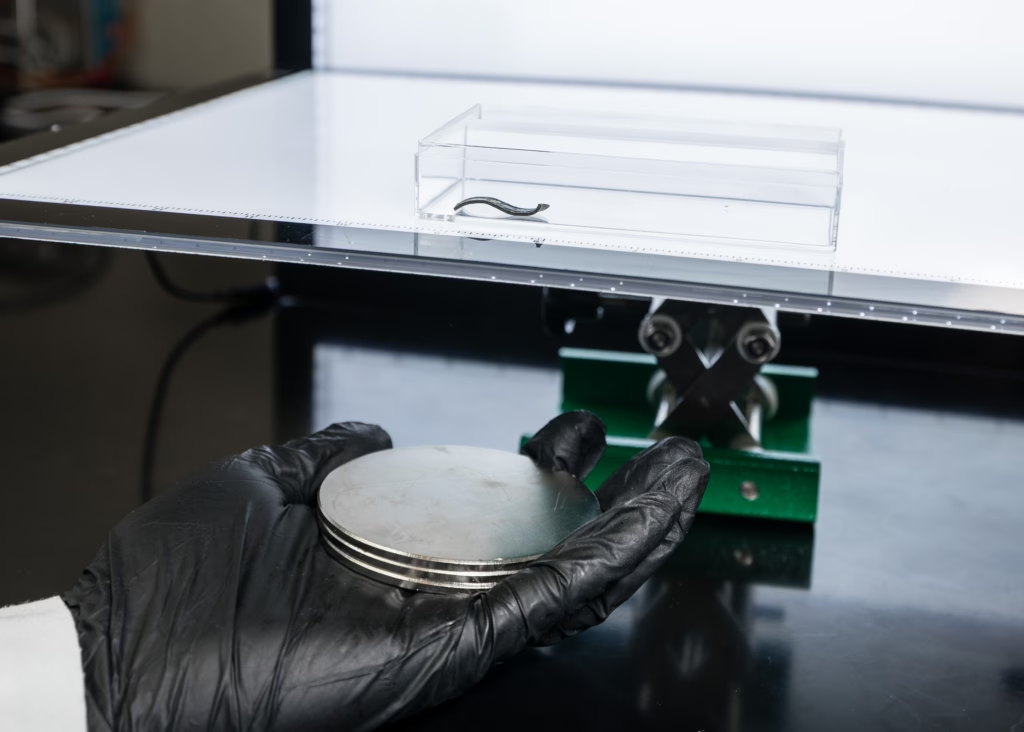

PhD student Youyi Zhou (also pictured at the top of the story with Assistant Professor Yunus Alapan) manipulates a soft robot using a magnet. Photos: Joel Hallberg.

PhD student Youyi Zhou (also pictured at the top of the story with Assistant Professor Yunus Alapan) manipulates a soft robot using a magnet. Photos: Joel Hallberg.