University of Wisconsin-Madison engineers have developed a new technology that can read a person’s pulse, blood pressure and oxygen saturation—remotely.

Unlike other remote biometric sensors, this new “hyperspectral imaging” technology can operate in real-world, ambient-light conditions, meaning it is unaffected by moving clouds, flickering screens and other uncontrolled sources of light.

It’s a big step toward personal health monitoring without the need for a wearable device. The advance also unlocks many other hyperspectral applications.

Led by Zongfu Yu, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at UW-Madison, and postdoctoral scholars Zewei Shao and Guoming Huang, the research appears in the Jan. 13, 2026, issue of the journal Nature Sensors.

Most imaging devices are tuned to pick up three types of light in the electromagnetic spectrum: the red, green and blue color bands. But that spectrum contains hundreds of bands of light—many beyond human perception—that can gather information about biological tissues, determine chemical composition, detect heat, and carry other data. In recent decades, researchers have developed sophisticated hyperspectral cameras that can collect a much broader swath of the electromagnetic spectrum—including important chemical and biological health information.

Until now, these hyperspectral cameras were a high-potential technology mostly confined to research labs. “The technology has improved rapidly, but it hasn’t been widely adopted for practical use,” says Yu. “That’s because in the lab, these measurements are made in perfect conditions with a $100,000 set up—but outside the lab, the ambient environment is beyond your control. There is all sorts of light illuminating your subject and getting into your sensor.”

In other words, existing hyperspectral cameras can’t handle ever-changing cloud cover, lights turning on and off, or errant shadows crossing their path. That’s why Yu and his colleagues took on the challenge of developing a portable, inexpensive hyperspectral device that can cope with the complex light conditions found in the real world.

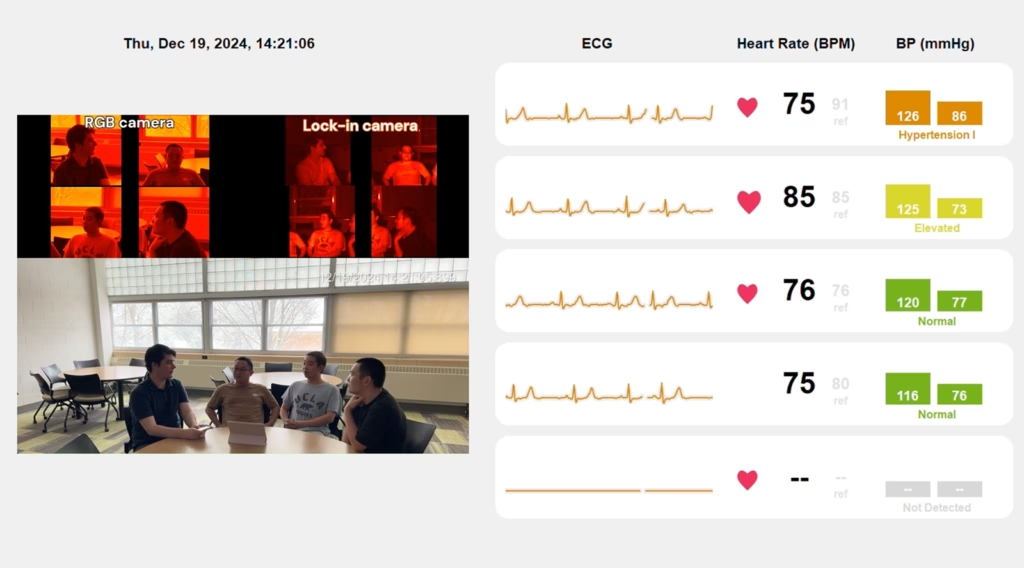

The researchers co-designed an LED system that emits a specially encoded illumination, along with a very-high-frequency, custom-designed lock-in CMOS chip—the semiconductor that collects information coming into the camera. The lock-in CMOS chip is tuned to recognize only the LED’s light and to ignore the rest of the ambient light bombarding the camera. This drastically reduces the signal-to-noise ratio—allowing the system to pick out only the signals in frequencies that are carrying useful information.

The results so far are very promising: The system can estimate heart rate with an error rate below three beats per minute and, using signals in the visible and infrared spectrums, blood oxygen saturation within 3%, both at a distance of 6 feet. Using machine learning algorithms, the system can use the information to reconstruct blood pressure with the same accuracy as wearable devices.

“There’s no fundamental reason you can’t use this from 20 feet or even 100 yards away,” says Yu. “It will just take some engineering effort.”

Yu and his team plan to continue making the device even more practical. Currently, their camera is about 6 inches square and draws 50 to 100 watts of energy. But with optimization and miniaturization, the researchers believe they can shrink the device down to the size of current cellphone cameras.

While this particular project showed the technology’s impact on health monitoring, Yu says it is just one demonstration of the potential power of hyperspectral imaging—a focus of his lab for the past decade. The same imaging platform could be used in cancer detection, tissue imaging, environmental monitoring, food safety, agricultural sensing and dozens of other applications. “Once you can accurately measure the spectral information of a subject without the influence of ambient light, then the promise of hyperspectral imaging can be carried outside the lab into real life,” says Yu. “It’s going to be very, very impactful.”

The lock-in sensor on the hyperspectral imaging system allows it to detect signals carrying information about pulse, oxygen levels and blood pressure, even in changing ambient light.

The lock-in sensor on the hyperspectral imaging system allows it to detect signals carrying information about pulse, oxygen levels and blood pressure, even in changing ambient light.

Zongfu Yu is the Grainger Professor in electrical and computer engineering. Other UW-Madison authors include Alexander Mielczarek, Qingyi Zhou and Henry Schnieders.

The authors acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health under award number 10450190.