While fantasies of mechanical maids aren’t yet reality, autonomous aides are emerging in a few areas of the modern world.

Highlight reels from the inaugural World Humanoid Robot Games, held in August 2025 in Beijing, show robots sprinting down a track, trading punches in a boxing ring, performing gymnastic-style flips, and more.

But if you watch more footage, you’ll also see a robot runner slam into the back of a human helper, a robot soccer game devolve into a metal pileup, and one robotic obstacle course contestant tumble down a set of stairs. For all the hype around robots—the Tesla events, the headlines about Amazon’s plans to replace more than half a million human workers, the cinematic videos—it turns out that pulling off humanlike performance is pretty darn hard.

Much less doing it autonomously.

“Popular culture makes it looks like robots work well,” says Mike Zinn, a professor of mechanical engineering who studies human-centered robotics. “And, honestly, for most aspects, there are still big performance problems.”

That’s not to say the field isn’t making significant progress.

Heavy, industrial robots have reshaped standardized assembly lines in industries like automobile manufacturing over the past several decades. More recently, though, collaborative robots, or “cobots,” have gained traction in auto plants as well as more customizable manufacturing lines—for example, in the aerospace industry, with the help of Zinn and Robert Radwin, the Duane H. and Dorothy M. Bluemke Professor of industrial and systems engineering.

Radwin’s group is demonstrating how cobots complement—rather than replace—manual labor while improving ergonomics and enhancing productivity, and that’s catching on. In October 2025, Wisconsin-headquartered Rockwell Automation announced it had produced its first autonomous mobile robots, designed to carry heavy materials and reduce forklift usage. Drones are more and more commonplace across industries. Robotic surgery systems are widely used in hospitals.

And startup companies and academic researchers alike continue to push robotics forward. Even if Jetson-like “Rosey the Robot” maids aren’t right around the corner, here are four ways robots—with the help of UW-Madison engineers—could take on larger roles in our world over the next decade:

Helpers with heavy lifting

While productivity in the manufacturing industry has continued to increase over the past two-and-a-half decades, the construction industry hasn’t followed suit. Large, specialized robots that can lay bricks have made some inroads and could take over one repetitive task. More versatile robots, though, could deliver materials to human workers around construction sites, rather than replacing their jobs.

“Human workers will make decisions and will do the high-level work and job planning,” says Zhenhua Zhu, the Mortenson Company Assistant Professor of civil and environmental engineering. “Then the robot will do some labor-intensive work.”

Zhu’s research group, for example, is analyzing the navigation algorithms used by one four-legged robot at the construction site of the new Kellner Family Athletic Center at UW-Madison. In another project, he and his students are looking at the interactions between construction workers and drones, which could be useful for delivering items at high-rise projects.

“Big construction companies are aware of robotic technologies,” says Zhu, “but we need to show them the return on investment and successful stories.”

Gut action

With a magnet and a small elastic polymer strip, healthcare providers could one day deliver a medicine—or even multiple, staggered treatments—to a precise location within a patient’s gastrointestinal tract.

Yunus Alapan, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering, is developing miniature, flexible, magnetic soft robots that, with guidance from external signals, could traverse different passages within the body. While they may not conform to the classical idea of robots, they can crawl, roll, jump and release cargo. Alapan estimates they could reach clinical trials within the next five years.

“In terms of the technology, I don’t think there’s a huge barrier,” he says. “As long as we address something that is needed and important. Also, in terms of regulation, we have these endoscopic tools already; we have pill cameras.”

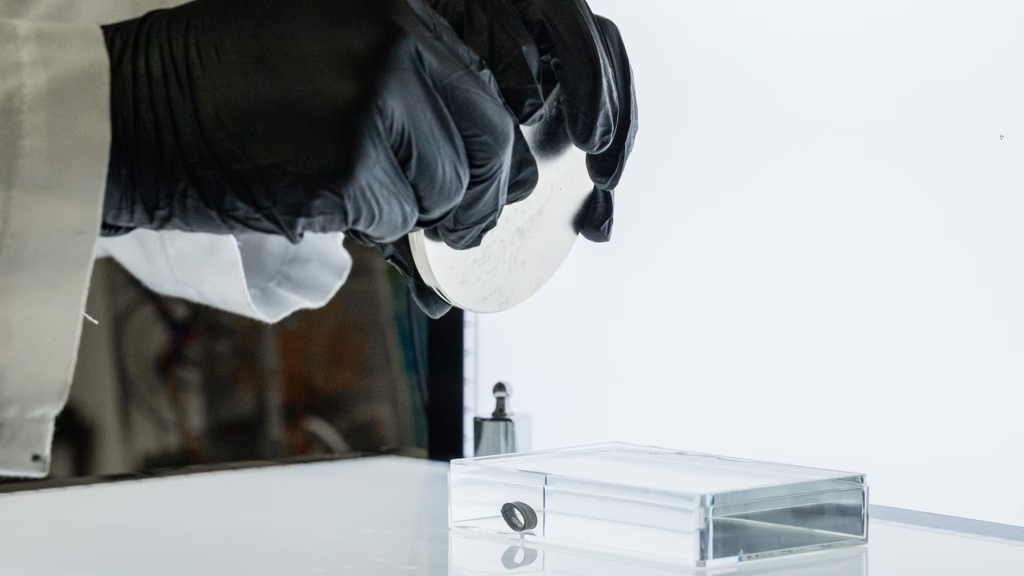

PhD student Youyi Zhou manipulates a soft robot using a magnet. Photo: Joel Hallberg.

PhD student Youyi Zhou manipulates a soft robot using a magnet. Photo: Joel Hallberg.

Ferries, themselves

Just as autonomous vehicles are advancing on land, similar technology is entering waterways. As a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Wei Wang worked on systems for aquatic autonomous robotics that helped spur a spinoff company that’s bringing the emerging tech to the canals of Amsterdam.

The startup, Roboat, has developed autonomous boats that could serve as water taxis, garbage collectors or ferries to bolster urban transportation. One such ferry has made trial deployments on the Seine River in Paris.

While Wang, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at UW-Madison since 2024, is no longer involved in the Roboat project, he’s continued his work on the control and perception algorithms that are essential for aquatic robots to navigate through water.

“This robot might encounter large waves, wind or current,” says Wang. “This harsh environment makes the control and perception of the system very, very challenging.”

Operation operatives

Robot-assisted surgeries have become standard practice in recent decades, particularly in specialties like urology at major medical centers. Intuitive Surgical’s da Vinci systems have established the company as the dominant player in the market.

Jackie Cha, an assistant professor of industrial and systems engineering who studies human-robot interactions in healthcare, says increased competition from upstarts in the industry could allow for wider adoption of robotic systems. She’s published work aimed at helping healthcare decision-makers better evaluate robotic surgery systems.

The design of such systems, in which a surgeon typically sits at a control console away from the patient, combined with advances in telecommunications networks, allows for another possibility: remote surgeries. In fact, they’ve already taken place, dating back all the way to 2001. Continued expansion of 5G wireless internet networks could, theoretically, allow a surgeon to remotely operate on patients living in rural areas—provided the robotic surgery system is delivered and set up.

“Adoption comes down to safe integration into clinical workflows,” Cha says. “Cost is one factor; having the system infrastructure to support what clinicians do is another.”

Top photo courtesy JP Cullen